Setbacks: 2025 has been a challenging year for the Open Library community and the library world. We began the year by upgrading our systems in response to cybersecurity incidents and fortifying our web services to withstand relentless DDOS (distributed denial of service) attacks from bots. We developed revised plans to achieve More with Less to meet the needs of patrons who lost access to 500,000 books due to late-2024 takedowns. The year continued to bring setbacks, including a Brussels Court order, which resulted in additional removals, and contesting thousands of spammy automated takedown requests from an AI company. Just last month, we responded to a power outage affecting one of our data centers and then a cut that was identified in one of our internet service provider’s fiberoptic cables, resulting in reduced access.

Given all these setbacks, why weren’t we seeing a decline in sign-ups?

Less is More: Putting patrons’ experience first. As the year progressed and we reviewed our quarterly numbers, one metric that circumstantially held high was sign-ups. The Open Library is historically a significant source of registrations for the Internet Archive, contributing to approximately 30% of all registrations. Some websites may have found it reassuring that, despite all the challenges presented in 2024 and 2025, adoption seemed to keep its pace. At the Open Library, we measure success in value delivered to readers — not registrations — and this trend seemed to indicated something may have become out of balance:

What reason(s) might explain why registrations remain steady when significant sources of value are no longer accessible?

We hypothesized some class of patrons are signing up with an expectation and then not getting the value they are expecting.

Testing the hypothesis: The first step of our investigation was to take inventory of the possible reasons one might register an account. Each of the following actions require accounts:

- Borrowing a book

- Using the Reading Log

- Adding books to Lists

- Community review tags

- Following other readers

- Reading Goals

Supporting Evidence: We started by reviewing the Reading Log because it’s the platform’s largest source of engagement, with 5M unique patrons logging 11.5M books. We discovered that millions of patrons had only logged a single book. There’s nothing inherently bad about this statistic, in fact many websites may be happy about this engagement. However, unlike many book catalog websites, the Open Library is unique in that it links to millions of books that may be accessed through trusted book providers. It is thus reasonable that many patrons come to the Open Library website with the intent of accessing a specific title. This data amplified occasional reports from patrons who expressed disappointed when clicking “Want to Read” did not result in access to the book.

Refined hypothesis: Based on these learnings, we felt confident the “Want to Read” button may be confusing new patrons who thought clicking the button would get them access to the book. Under this lens, each of these registrations represents adoption for the wrong reason: i.e. a patron is compelled by the offering to register, but they bounce because what they get is a broken promise.

Trying a solution: Data gave us confidence the “Want to Read” button may be confusing new visitors to the site, but it also revealed that hundreds of thousands of patrons are actively using the Reading Log to keep track of books and we didn’t want to confuse the experience for them. We decided to change the website so that non-logged-in patrons, would see the “Want to Read” button as “Add to List” instead, whereas logged-in returning visitors would continue to see the “Want to Read” button they were used to.

Results: When our team launched this week’s deploy, we noticed a few performance hiccups: our latest deploy increased memory demands and our servers began using too much memory, causing swapping. After some fire-fighting, we were able to make adjustments to our workers that normalized performance, though we remained alert.

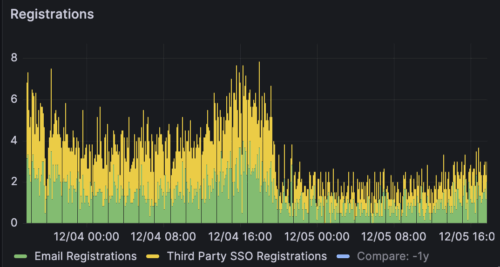

Later that night, we noticed a significant drop in registrations and started frantically testing the website:

We were thrilled to realize that our services are working correctly and the chart accurately reflected — what we hope to be — a decrease in bad experiences for our patrons.

Conclusion: Sometimes, less is more. We anticipate this will be the first small change in a long series of marginal improvements we hope to bring us closer into alignment with the core needs of our patrons. As we move towards 2026, we will continue to respond to the new normal shaped by recent events with the mantra: back to basics.