A forward by Drini Cami

Drini Cami here, Open Library staff developer. It’s my pleasure to introduce Rebecca Shoptaw, a 2024 Open Library Engineering Fellow, to the Open Library blog in her first blog post. Rebecca began volunteering with us a few months ago and has already made many great improvements to Open Library. I’ve had the honour of mentoring her during her fellowship, and I’ve been incredibly impressed by her work and her trajectory. Combining her technical competence, work ethic, always-ready positive attitude, and her organization and attention to detail, Rebecca has been an invaluable and rare contributor. I can rely on her to take a project, break it down, learn anything she needs to learn (and fast), and then run it to completion. All while staying positive and providing clear communication of what she’s working on and not dropping any details along the way.

In her short time here, she has also already taken a guidance role with other new contributors, improving our documentation and helping others get started. I don’t know how you found us, Rebecca, but I’m very glad you did!

And with that, I’ll pass it to Rebecca to speak about one of her first projects on Open Library: improving our translation/internationalization pipeline.

Improving Open Library’s Translation Pipeline

Picture this: you’re browsing around on a site, not a care in the world, and suddenly out of nowhere you are told you can “cliquez ici pour en savoir plus.”

Maybe you know enough French to figure it out, maybe you throw it into Google Translate, maybe you can infer from the context, or maybe you just give up. In any of these cases, your experience of using the site just became that much less straightforward.

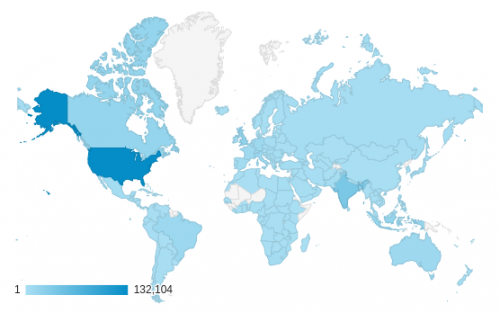

This is what the Open Library experience has been here and there for many non-English-speaking readers. All our translation is done by volunteers, so with over 300 site contributors and an average of 40 commits added to the codebase each week, there has typically been some delay between new text getting added to the site and that text being translated.

One major source of this delay was on the developer side of the translation process. To make translation of the site possible, the developers need to provide every translator with a list of all the phrases that will be visible to readers on-screen, such as the names of buttons (“Submit,” “Cancel,” “Log In”), the links in the site menu (“My Books,” “Collections,” “Advanced Search”), and the instructions for adding and editing books, covers, and authors. While updates to the visible text occur very frequently, the translation “template” which lists all the site’s visible phrases was previously only updated manually, a process that would usually happen every 3-6 months.

This meant that new text could sit on the site for weeks or months before our volunteer translators were able to access it for translation. There had to be a better way.

And there was! I’m happy to report that the Open Library codebase now automatically generates that template file every time a change is made, so translators no longer have to wait. But how does it work, and how did it all happen? Let’s get into some technical details.

How It Began

Back in February, one of the site’s translators requested an update to the template file so as to begin translating some of the new text. I’d done a little developer-side translation work on the site already, so I was assigned to the issue.

I ran the script to generate the new file, and right away noticed two things:

- The process was very simple to run (a single command), and it ran very quickly.

- The update resulted in a 2,132-line change to the template file, which meant it had fallen very, very out of date.

I pointed this out to the issue’s lead, Drini, and he mentioned that there had been talk of finding a way to automate the process, but they hadn’t settled on the best way to do so.

I signed off and went to make some lunch, then ran back and suggested that the most efficient way to automate it would be to check whether each incoming change includes new/changed site text, and to run the script automatically if so. He liked the idea, so I wrote up a proposal for it, but nothing really came of it until:

The Hook

In March, Drini reached back out to me with an idea about a potentially simple way to do the automation. Whenever a developer submits a new change they would like to make to the code, we run a set of automatic tests, called “pre-commit hooks,” mostly to make sure that their submission does not contain any typos and would not cause any problems if integrated into the site.

Since my automation idea had been to update the translation template each time a relevant change was made, Drini suggested that the most natural way to do that would be to add a quick template re-generation to the series of automated tests we already have.

The method seemed shockingly simple, so I went ahead and drafted an implementation of it. I tested it a few times on my own computer, found that it worked like a charm, and then submitted it, only to encounter:

The Infinite Loop of Failure

Here’s where things got interesting. The first version of the script simply generated a new template file whether or not the site’s text had actually been changed – this made the most sense since the process was so fast and if nothing actually had changed in the template, the developer wouldn’t notice a difference.

But strangely enough, even though my changes to the code didn’t include any new text, I was failing the check that I wrote! I delved into the code, did some more research into how these hooks work, and soon discovered the culprit.

The process for a simple check and auto-fix usually works as follows:

- When the change comes in, the automated checks run; if the program notices that something is wrong (i.e. extra whitespace), it fixes any problems automatically if possible.

- If it doesn’t notice anything wrong and/or doesn’t make any changes, it will report a success and stop there. If it notices a problem, even if it already auto-fixed it, it will report a failure and run again to make sure its fix was successful.

- On the second run, if the automatic fix was successful, the program should not have to make any further changes, and will report a success. If the program does have to make further changes, or notices that there is still a problem, it will fail again and require human intervention to fix the problem.

This is the typical process for fixing small formatting errors that can easily be handled by an automation tool. But in this case, the script was running twice and reporting a failure both times.

By comparing the versions of the template, I discovered that the problem was very simple: the hook is designed, as described above, to report a failure and re-run if it has made any changes to the code. The template includes a timestamp that automatically lists when it was last updated down to the second. When running online, because more pre-commit checks are run than when running locally, pre-commit takes long enough that by the time it runs again, enough seconds have elapsed that it generates a new timestamp, causing it to notice a one-line difference between the current and previous templates (the timestamp itself), and so it fails again. I.e.:

- The changes come in, and the program auto-updates the translation template, including the timestamp.

- It notices that it has made a change (the timestamp and any new/changed phrases), so it reports a failure and runs again.

- The program auto-updates the translation template again, including the timestamp.

- It notices that it has made a change (the timestamp has changed), and reports a second failure.

And so on. An infinite loop of failure!

We could find no way to simply remove the timestamp from the template, so to get out of the infinite loop of failure, I ended up modifying the script so that it actually checks whether the incoming changes would affect the template before updating it. Basically, the script gathers up all the phrases in the current template and compares them to all the incoming phrases. If there is no difference, it does nothing and reports a success. If there is a difference, i.e. if the changes have added or changed the site’s text, it updates the template and reports a failure, so that now:

- The changes come in, and the program checks whether an auto-update of the template would have any effect on the phrases.

- If there are no phrase changes, it decides not to update the template and reports a success. If there are phrase changes, it auto-updates the template, reports a failure and runs again.

- The program checks again whether an auto-update would have any effect, and this time it will not (since all the new phrases have been added), so it does not update the template or timestamp, and reports a success.

What it looks like locally:

I also added a few other options to the script so that developers could run it manually if they chose, and could decide whether or not to see a list of all the files that the script found translatable phrases in.

The Rollout

To ensure we were getting as much of the site’s text translated as possible, I also proposed and oversaw a bulk formatting of a lot of the onscreen text which had previously not been findable by the template-updating function. The project was heroically taken on by Meredith (@merwhite11), who successfully updated the formatting for text across almost 100 separate files. I then did a full rewrite of the instructions for how to format text for translation, using the lessons we learned along the way.

When the translation automation project went live, I also wrote a new guide for developers so they would understand what to expect when the template-updating check ran, and answered various questions from newer developers re: how the process worked.

The next phase of the translation project involved using the same automated process we figured out to update the template to notify developers if their changes include text that isn’t correctly formatted for translation. Stef (@pidgezero-one) did a fantastic job making that a reality, and it has allowed us to properly internationalize upwards of 500 previously untranslatable phrases, which will make internationalization much easier to keep track of for future developers.

When I first updated the template file back in February of this year, it had not been updated since March of the previous year, about 11 months. The automation has now been live since May 1, and since then the template has already been auto-updated 35 times, or approximately every two to three days.

While the Open Library translation process will never be perfect, I think we can be very hopeful that this automation project will make une grosse différence.