We’ve all heard the advice, don’t judge a book by its cover. But then how should we go about identifying books which are good for us? The secret depends on understanding two things:

- What is a book?

- What are our preferences?

We can’t easily answer the second question without understanding the first one. But we can help by being good library listeners and trying to provide tools, such as the Reading Log and Lists, to help patrons record and discover books they like. Since everyone is different, the second question is key to understanding why patrons like these books and making Open Library as useful as possible to patrons.

What is a book?

As we’ve explored before, determining whether something is a book is a deceptively difficult task, even for librarians. It’s a bound thing made of paper, right? But what about audiobooks and ebooks? Ok, books have ISBNs right? But many formats can have ISBNs and books published before 1967 won’t have one. And what about yearbooks? Is a yearbook a book? Is a dictionary a book? What about a phonebook? A price guide? An atlas? There are entire organizations, like the San Francisco Center for the Book, dedicated to exploring and pushing the limits of the book format.

In some ways, it’s easier to answer this question about humans than books because every human is built according to a specific genetic blueprint called DNA. We all have DNA, what make us unique are the variations of more than 20,000 genes that our DNA are made of, which help encode for characteristics like hair and eye color. In 1990, an international research group called the Human Genome Project (HGP) began sequencing the human genome to definitively uncover, “nature’s complete genetic blueprint for building a human being”. The result, which completed in 2003, was a compelling answer of, “what is a human?”.

Nine years later, Will Glaser & Tim Westergren drew inspiration from HGP and launched a similar effort called the Music Genome Project, using trained experts to classify and label music according to a taxonomy of characteristics, like genre and tempo. This system became the engine which powers song recommendations for Pandora Radio.

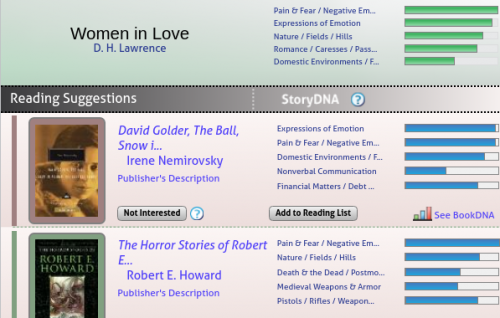

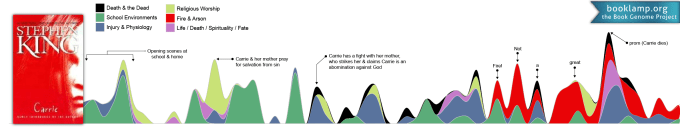

Circa 2003, Aaron Stanton, Matt Monroe, Sidian Jones, and Dan Bowen adapted the idea of Pandora to books, creating a book recommendation service called BookLamp. Under the hood, they devised a Book Genome Project which combined computers and crowds to “identify, track, measure, and study the multitude of features that make up a book”.

Their system analyzed books and surfaced insights about their structure, themes, age-appropriateness, and even pace, bringing us withing grasping distance of the answer to our question: What is a book?

Sadly, the project did not release their data, was acquired by Apple in 2014, and subsequently discontinued. But they left an exciting treasure map for others to follow.

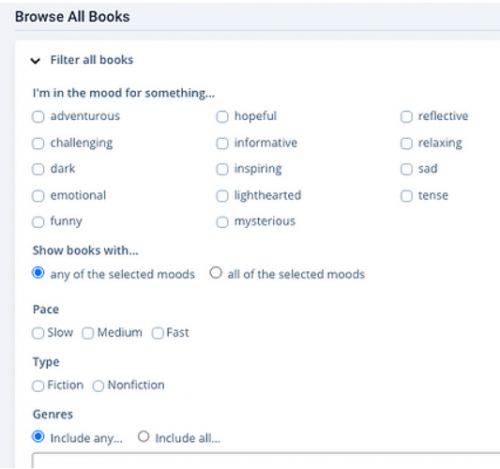

And follow, others did. In 2006, a project called the Open Music Genome Project attempted to create a public, open, community alternative to Pandora’s Music Genome Project. We thought this was a beautiful gesture and a great opportunity for Open Library; perhaps we could facilitate public book insights which any project in the ecosystem could use to create their own answer for, “what is a book?”. We also found inspiration from complimentary projects like StoryGraph, which elegantly crowd sources book tags from patrons to help you, “choose your next book based on your mood and your favorite topics and themes”, HaithiTrust Research Center (HTRC) which has led the way in making book data available to researchers, and the Open Syllabus Project which is surfacing useful academic books based on their usage across college curriculum.

Introducing the Open Book Genome Project

Over the last several months, we’ve been talking to communities, conducting research, speaking with some of the teams behind these innovative projects, and building experiments to shape a non-profit adaptation of these approaches called the Open Book Genome Project (OBGP).

Our hope is that this Open Book Genome Project will help responsibly make book data more useful and accessible to the public: to power book recommendations, to compare books based on their similarities and differences, to produce more accurate summaries, to calculate reading levels to match audiences to books, to surface citations and urls mentioned within books, and more.

OBGP hopes to achieve these things by employing a two pronged approach which readers may continue learning about in following two blog posts:

- The Sequencer – a community-engineered bot which reads millions of Internet Archive books and extracts key insights for public consumption.

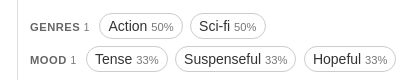

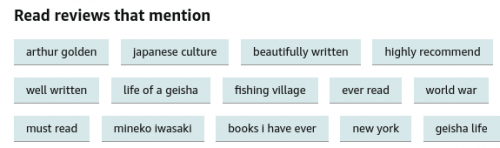

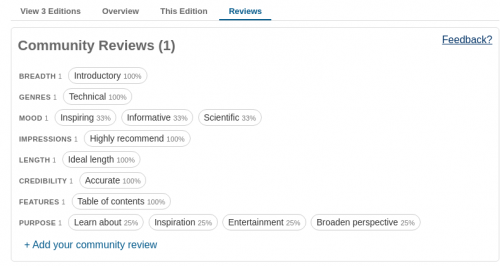

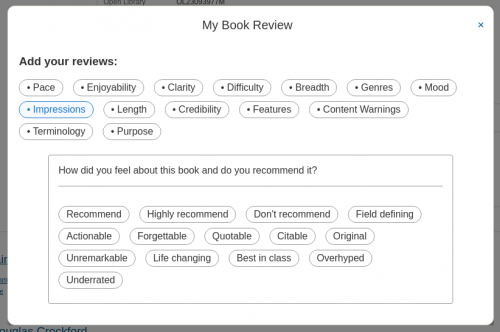

- Community Reviews – a new crowd-sourced book tagging system which empowers readers to collaboratively classify & share structured reviews of books.

Or hear an overview of the OBGP in this half-hour tech talk: