A team of volunteer Open Librarians have worked together to organize the many Nancy Drew book series into a beautiful collection on Open Library.

If you’re excited about this collection, you can direct your thanks to Open Library volunteer Emily, who proposed the project. A few months ago, Emily put out a call in Open Library’s librarian Slack channel to see if other librarians might be interested in teaming up. Today, the collection is live and ready for the benefit of the public.

A collaborative approach was second nature for Emily, a librarian and educator who recently completed a Master of Information program.

“Almost all of our projects were group work to help prepare us to work together and collaborate in libraries,” she said.

To organize the project, Emily built a detailed Google Document with information, ideas, questions about methodology and choices the team would need to make as a group. Participants added thoughts and notes asynchronously before the call.

An initial Zoom call then brought the team of volunteers together in real time. The call was held in a time zone that worked for the international contributors, who came from Tokyo, Pakistan and the western U.S.

“I think it was really important to do a video call to start things off, just to really just humanize everyone,” Emily said. “Like you see everyone a little bit, you hear their voices, you know that you’re working together. You know that you’re a team, and that helps everyone stay motivated.”

Maahin, located in Pakistan, worked on two series of the collection, Nancy Drew and the Clue Crew and Nancy Drew Notebooks. She had long wanted to become a librarian. “Being in a place where there’s no scope of reading and related professions, Open Library is the best chance to contribute in book-related tasks, and it motivated me finding you can contribute to it remotely,” she said.

On the kickoff call, contributors aligned on preliminary decisions, discussed how to divide the work and shared their reasons for contributing.

How best to build the collection required some sleuthing. Contributors explored various methods to build collections and tag large numbers of works. They considered using Python scripts to automate finding books and adding metadata, but determined the approach was impractical given the extensive metadata cleaning and large-scale review this project required, combined with limitations in their current technical expertise. In addition, they experimented with alternative versions of the current carousel code. However, they found that these new versions would result in a lag when users loaded the page. Contributors wanted to make sure the collection would be accessible to anyone, regardless of their Internet speed.

Because this was such a large collection with so many different series, Emily checked behind the scenes to learn how similar collections in Open Library had been built.

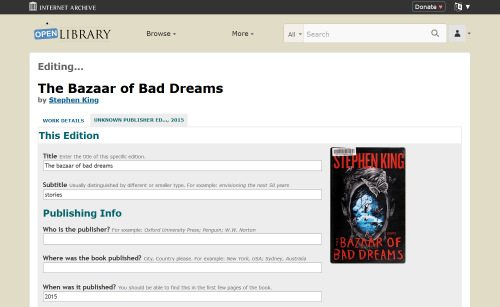

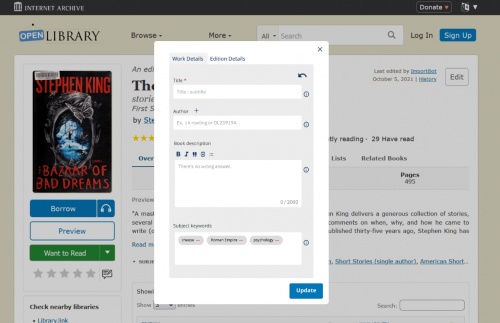

With that info in view, a decision was made to manually tag books’ subject fields with a collectionid: tag for each series.

Nichole, who focused on the Nancy Drew: Girl Detective and Nancy Drew on Campus series of the collection, joined the project out of a desire to learn.

“I was new to the Open Library and wanted to learn how to create collections and hone my metadata editing skills,” she said “I also noticed that we had a Hardy Boys series but not a Nancy Drew series, which felt like a gap.”

Working on metadata taught Nichole about source verification. Most of her previous metadata assignments involved checking single documents or websites, so she assumed the task of editing metadata for a series of books would be straightforward. But this project required evaluating and aggregating information from multiple sources.

“It was surprisingly challenging to confirm basic facts (like how many editions of a Nancy Drew book exist and how they were published) and find reliable information.”

Another volunteer, Liz, consulted portions of the book, “Girl Sleuth: Nancy Drew and the Women Who Created Her” by Melanie Rehak. The biography identified another of the major challenges for the collection–many of the Nancy Drew books in Open Library had been attributed to the wrong ghostwriter, instead of the pen name Carolyn Keene. The pen name refers to numerous ghostwriters across different works and editions of the books (such as reissues). But most of the books in the library attributed the wrong ghostwriter as the author.

Lead Staff Librarian Lisa Seaberg helped to correct conflated author metadata, a common issue when a pseudonym is shared by multiple authors and when multiple authors have the same name.

The collection as it stands represents many hours of metadata cleanup from each of the contributors.

For future groups collaborating on collections, Emily suggests live-demo-ing how to edit the metadata before asking people to do it. “I think we all had to go on an individual journey of reading the documentation and figuring out how to do it,” Emily said.

Contributors each had their own reasons for helping to bring the Nancy Drew collection to life.

“For me, there’s definitely some nostalgia,” Nichole said. “I grew up during the era of Nancy Drew PC games and remember playing Nancy Drew: The Phantom of Venice. But I also appreciate Nancy Drew as a character. Growing up, I read a lot of detective fiction and became familiar with detectives like Sherlock Holmes, Hercule Poirot, Miss Marple, S. S. Van Dine and Hajime Kindaichi. Nancy Drew feels unique — not just in age and life experience but also in personality and technique.”

Emily grew up on a small dairy farm in rural Canada, without access to many TV channels. “It was just so nice to have these stories that I could access — this huge wealth of narratives about a woman who was really curious,” Emily said. “It was just a really good role model for me growing up.”

Maahin joined for the chance to do library work. “I am excited to work on all kinds of tasks including documentation and cataloguing and every other thing that is related to books and library,” she said.

Work on the collection and cleanup of metadata in the current collection is still ongoing, with continuing opportunities to contribute. Some of these include adding series tags or special featured collections, such as the books that inspired the Nancy Drew computer game series.

Emily also aspires to make the books appear in order in the series. (Currently the order is tied to the date of the most recent edition.) “If we could find a developer who can find a solution to help us make all these books appear in order in the series, that would be wonderful,” Emily said.

The project took months from start to finish. The work to clean metadata and get the first eight series of 500-plus books into the collection was substantial, but rewarding.

“It was work to learn how to do it, but it is so satisfying to have built something and help share the things that helped you have a love of reading with other people,” Emily said. “And it’s been really wonderful to connect with similarly minded people as well.”

If you would like to contribute to this or future collections projects at Open Library, fill out this volunteer form.

Lessons Learned:

- How to Build Collections: For now, manually tagging books’ subject fields with a collectionid: tag for each series, and copying the code from past multi-series collections, is the most expedient way to build a collection.

- Human Connection Matters: Meeting fellow librarians, combined with defined asynchronous processes, can help a collaborative project go smoothly.

- Live Training Could Save Time: Future projects would benefit from a short live demonstration of metadata editing at the outset. This could reduce the learning curve and help volunteers feel confident contributing sooner.