Dana, UX/Design Fellow on Open Library

Forward by Mek

Few aspects of a website have greater impact and receive less recognition than good navigation. If done well, a site’s main navigation is almost invisible: it’s there when patrons need it, out of the way when they don’t, and it zips patrons to the right place without making them overthink. Over the years, we’ve attempted improvements to our navigation but we haven’t had the design bandwidth to conduct user research and verify that our changes solved our patrons problem. It turns out, we still had several opportunities for improvement. That’s why this year we were incredible lucky to have collaborated with Open Library UX Design Fellow Dana Fein-Schaffer, who recently transitioned into design from a previous role as a neuropsychological researcher. Dana’s formal education and experience links a trifecta of complimentary fields — computer science, psychology, and design — and has resulted in unique perspective as we’ve endeavored to redesign several of Open Library’s core experiences: the website’s main navigation and the desktop version of our My Books page.

As an Open Library UX Design Fellow, Dana has been in charge of design direction, conducting user interviews, figma mockups, feedback sessions, and communicating decisions to stakeholders. In addition to her skill prototyping and notable problem solving capabilities, Dana’s warmth with the community, affinity for collaboration, and enthusiasm for the project has made teaming up with her a gift. While we’d rather the fellowship not end, we endorse her work with great enthusiasm and highly recommend organizations which share our values to view Dana’s portfolio and engage her for future design opportunities.

The Design Process

Hello, I’m Dana Fein-Schaffer, and I’ve been working as a UX Design Fellow with Open Library over the past several months. I’m currently transitioning into UX Design because after gaining professional experience in both psychology research and software engineering, I’ve realized that UX is the perfect blend of my skills and interests. I’ve been enjoying growing my UX skillset, and working with Open Library has been a perfect opportunity for me to gain some formal experience because I love reading and was hoping to work on a book-related project. Moving forward, I’m particularly excited about working as a UX designer for an organization that focuses on social good, especially in the literary, education, or healthcare spaces! If you have a role that may be a good fit, or if you work in one of those industries and are interested in connecting, please feel free to reach out. You can also learn about me from my portfolio.

Problem

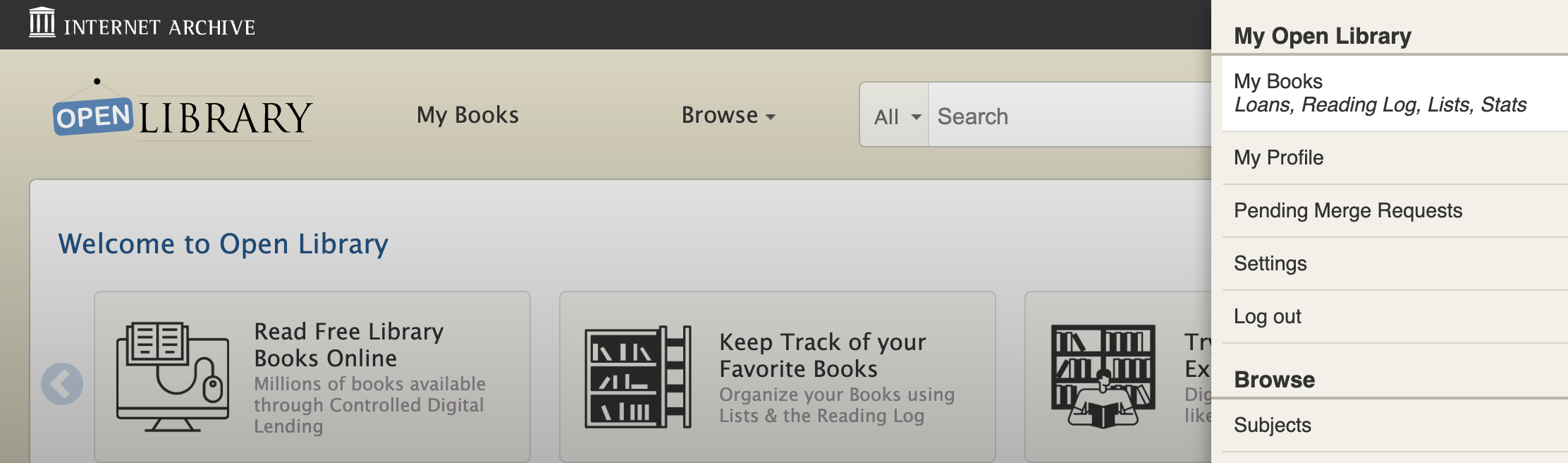

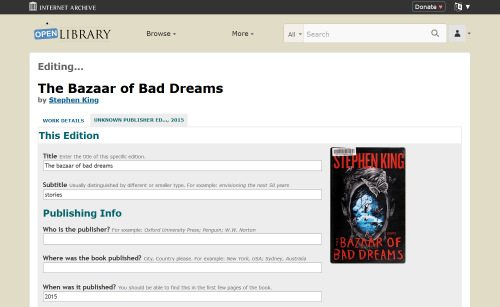

At the beginning of my project, the current navigation bar and hamburger menu looked like this:

I met with members of the Open Library team to identify three key areas of concern:

- The label “more” was not descriptive, and it was unclear to patrons what this meant

- The hamburger menu was not consistent with the navigation bar items

- The hamburger menu was confusing for patrons, especially new patrons, to navigate

Approach

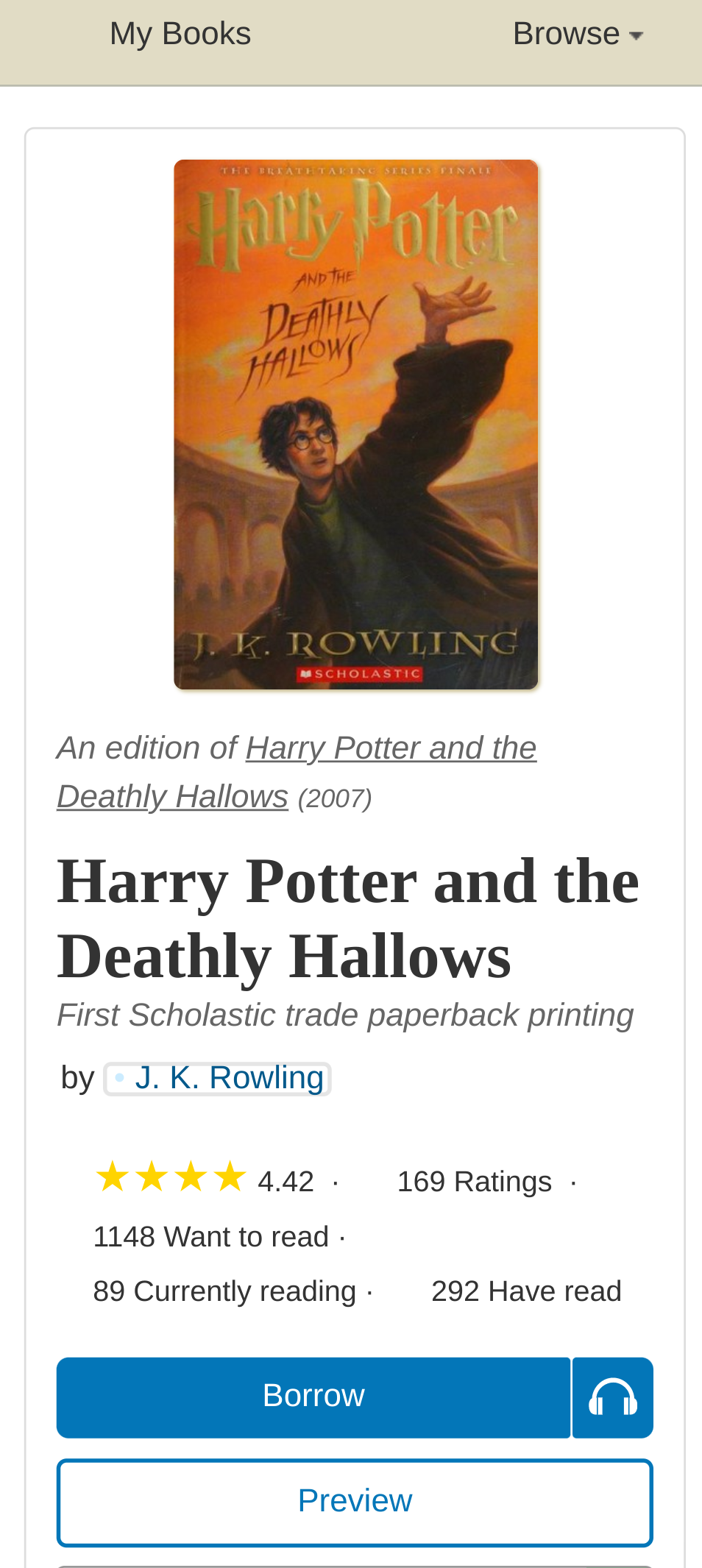

Before I began my project, the Open Library team decided to implement an interim solution to the first point above. To address the concern with the “more” label, the navigation menu was changed to instead include “My Books” and “Browse.” The website analytics showed that patrons frequent their Loans page most, so for now, the “My Books” page brings patrons to the Loans page.

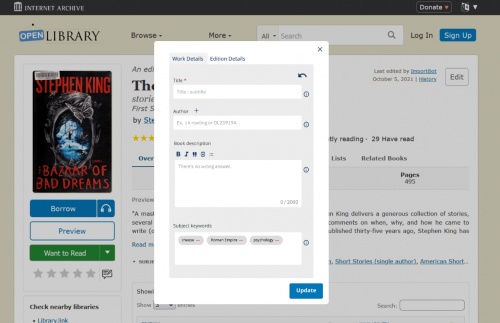

To begin redesigning the main site navigation, I first created a prototype in Figma with some potential solutions that built off of this updated navigation menu:

- I created a dropdown menu for “My Books” that would allow patrons to select the specific page they would like to go to, rather than automatically going to the Loans page

- I reorganized the hamburger menu to be consistent with the navigation menu and to use the subheadings of “Contribute” and “Resources” instead of “More.” I felt that these changes would make the hamburger menu easier to navigate for both new and long-time patrons.

After creating the prototype, my next goal was to get feedback from patrons, so I scheduled user interviews with volunteers.

User Interviews

I conducted user interviews via Zoom with four patrons to answer the following questions:

- How do users feel about the My Books dropdown?

- Are users using My Books and Browse from the navigation menu or hamburger menu?

- Are users able to effectively use the hamburger? Do they find it easier or harder to find what they’re looking for using the reorganized hamburger?

Results & Findings

- Three out of the four patrons preferred the dropdown, and the fourth user didn’t have a preference between the versions. The patrons enjoyed having the control to navigate to a specific section of My Books.

- All users used the navigation menu at the top of the page to navigate, rather than the hamburger menu, which supported the switch to “My Books” instead of “More.” This finding also highlighted the need to make sure patrons could access the pages they wanted to access from the top navigation menu.

- Finally, all four patrons found the existing hamburger menu confusing and preferred the reorganized hamburger. Some patrons specifically mentioned that the reorganized hamburger was more compact and that they felt that the headings “contribute” and “resources” were more clear than “more.”

Synthesis and a New Direction

After learning from the user interviews that patrons preferred increased granularity for accessing My Books and a more concise hamburger menu, the Open Library team began discussing the exact implementation. We wanted to keep the navigation and hamburger menus consistent; however, we also wanted to provide many options in the My Books dropdown, which made the hamburger menu less concise.

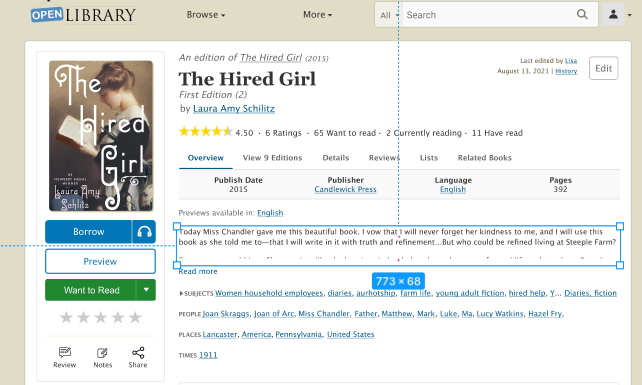

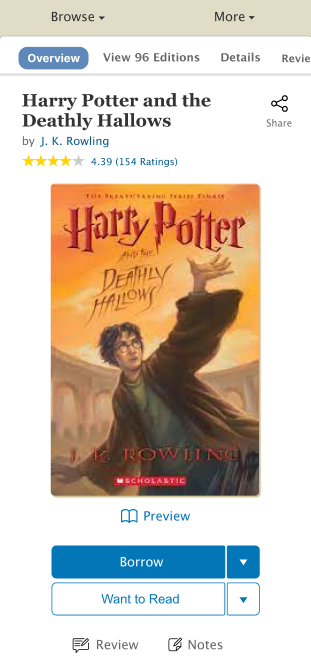

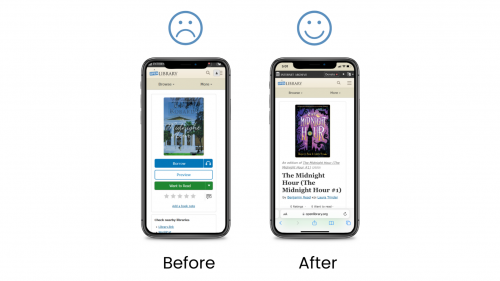

At the same time that we were debating the pros and cons of various solutions, another Open Library UX Design fellow, Samuel G, was working on designing a My Books landing page for the mobile site. Inspired by his designs, I created mockups for a desktop version of the My Books page. Having a My Books page that summarizes patrons’ loans, holds, and reading log at a glance allows patrons to still have increased control over My Books navigation while keeping the hamburger menu concise, since all of the individual My Books items can now be condensed into one link.

Furthermore, having a My Books landing page opens the door for more ways for patrons to interact with their reading through Open Library. For instance, I’ve created a mockup that includes a summary of a patron’s reading stats and yearly reading goal at the top of the page.

As we work towards implementing this design, I’m looking forward to getting feedback from patrons and brainstorming even more ways to maximize the use of this page.

Reflections

Working with the Open Library team has been an amazing experience. I’m so grateful that I got to lead a UX project from start to end, beginning with user research and ending with final designs that are ready to be implemented. Working with such a supportive team has allowed me to learn more about the iterative design process, get comfortable with sharing and critiquing my designs, and gain more experience with design tools, such as Figma. It was also a great learning experience that sometimes your projects will take an unexpected turn, but those turns help you eventually come to the best possible design solution. Thank you to everyone who provided feedback and helped me along the way, especially Mek, who was a wonderful mentor, and Sam, who was a great collaborator on our My Books mobile and desktop project!

About the Open Library Fellowship Program

The Internet Archive’s Open Library Fellowship is a flexible, self-designed independent study which pairs volunteers with mentors to lead development of a high impact feature for OpenLibrary.org. Most fellowship programs last one to two months and are flexible, according to the preferences of contributors and availability of mentors. We typically choose fellows based on their exemplary and active participation, conduct, and performance within the Open Library community. The Open Library staff typically only accepts 1 or 2 fellows at a time to ensure participants receive plenty of support and mentor time. Occasionally, funding for fellowships is made possible through Google Summer of Code or Internet Archive Summer of Code & Design. If you’re interested in contributing as an Open Library Fellow and receiving mentorship, you can apply using this form or email openlibrary@archive.org for more information.