Over the course of 2023, the Open Library team conducted design research and video-interviewed nine volunteers to determine how learners and educators make use of the OpenLibrary.org platform, what challenges get in their way, and how we can help them succeed. Participants of the study included a mix of students, teachers, and researchers from around the globe, spanning a variety of disciplines.

About the Participants

At the earliest stages of this research, a screener survey involving 466 participants helped us understand the wide range of patrons who use the Open Library. Excluding 141 responses that didn’t match the criteria of this research, the remaining 325 respondents identified as:

- 126 high school, university, or graduate students

- 64 self learners

- 44 researchers

- 41 K-12 teachers

- 29 professors

- 12 parents of K-12 students

- 9 librarians

Participants reported affiliations with institutions spanning a diverse variety of geographies, including: Colombia, Romania, France, Uganda, Indonesia, China, India, Botswana, Nigeria, and Ireland.

Findings

Here are the top 7 learnings we discovered from this research:

- The fact that the Open Library is free and accessible online is paramount to patrons’ success. During interviews, several participants told us that the Open Library helps them locate hard to find books they have difficulty finding elsewhere. At least two participants didn’t have access to a nearby library or a book vendor that could provide the book they needed. In a recent Internet Archive blog post, several patrons corroborated these challenges. In addition to finding materials, one or more of our participants are affected by disabilities or have worked with such persons who have limited mobility, difficulty commuting, and benefit from online access. Research use cases also drove the necessity for online access: At least two interviewed participants used texts primarily as references to cite or verify certain passages. The ability to quickly search for and access specific, relevant passages online was essential to helping them to succeed at their research objective, which may have otherwise been prohibitively expensive or technologically intractable.

- Participants voiced the importance of internationalization and having books in multiple languages. Nearly every participant we interviewed advocated for the website and books to be made available in more languages. One participant had to manually translate sections of English books into Arabic for their students. Another participant who studied classic literature manually translated editions so they could be compared. A teach who we interviewed relayed to us that it was common for their ESL (English as a Second Language) students to ask for help translating books from English into their primary language.

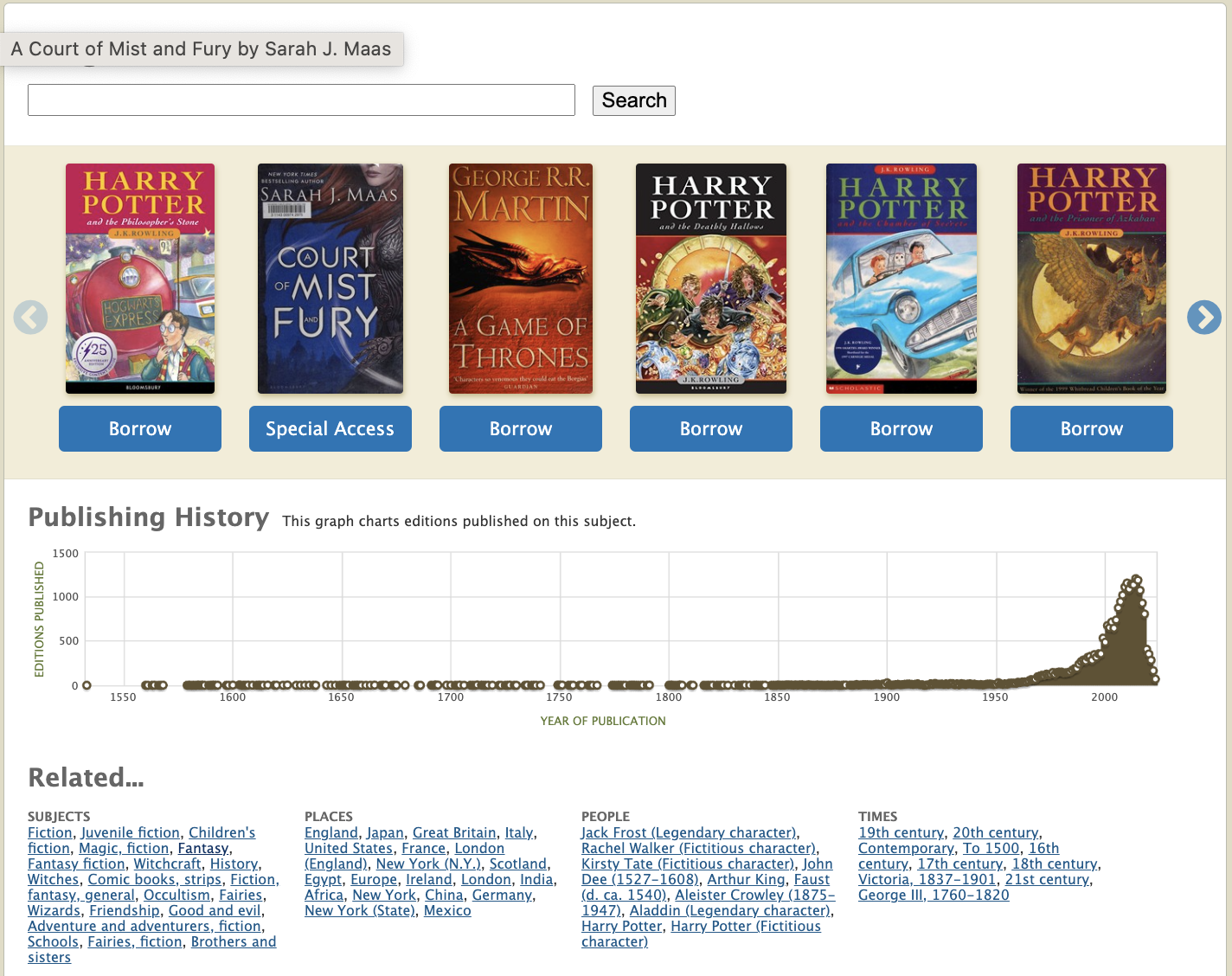

- The interests of learners and educators who use the Open Library vary greatly. We expected to find themes in the types of books learners and educators are searching for. However, the foci of participants we interviewed spanned a variety of topics, from Buddhism, to roller coaster history, therapy, technical books, language learning materials, and classic literature. Nearly none of our candidates were looking for the same thing and most had different goals and learning objectives. One need they all have in common is searching for books.

- The Open Library has many educational applications we hadn’t intended. One or more participant reported they had used the read aloud feature in their classroom to help students with phonics and language learning. While useful, participants also suggested the feature sometimes glitches and robotic sounding voices are a turnoff. We also learned several educators and researchers link to Open Library when creating course syllabi for their students.

- Many of Open Library subject and collection pages weren’t sufficient for one or more of our learners and educators use cases. At least two interviewees ended up compiling their own collections using their own personal web pages and linking back to the Open Library. One participant tried to use Open Library to search for K-12, age-appropriate books pertaining to the “US Constitution Day” and was grateful for but underwhelmed by the results.

- The Open Library service & its features are difficult to discover.

- Several interviewees were unaware of Open Library’s full-text search, read aloud, or note-taking capabilities, yet expressed interest in these features.

- Many respondents of the screener survey believed their affiliated institutions were unaware of the Open Library platform.

- Open Library’s community is generous, active, and eager to participate in research to help us improve. Overall, 450+ individuals from 100+ institutions participated in this process. Previously, more than 2k individuals helped us learn how our patrons prefer to read and more than 750 participants helped us redesign our book pages.

Some of our learnings we had already predicted and seeing these predictions confirmed by data has also given us conviction in pursuing next steps. Some learnings were genuinely surprising to us, such as many teachers preferring the online web-based book reader because it doesn’t require them to install any extra software on school computers.

Proposals

After reviewing this list of findings and challenges, we’ve identified 10 areas where the Open Library may be improved for learners and educators around the globe:

- Continuing to make more books available online by expanding our Trusted Book Providers program and adding Web Books to the catalog.

- Participating in outreach to promote platform discovery & adoption. Connect with institutions and educators to surface opportunities for partnership, integration, and to establish clear patterns for using Open Library within learning environments.

- Adding onboarding flow after registration to promote feature discovery. Conduct followup surveys to learn more about patrons, their challenges, and their needs. Add an onboarding experience which helps newly registered patrons become familiar with new services.

- Making books available in more languages by prototyping the capability to translate currently open pages within bookreader to any language, on-the-fly.

- Creating better subject and collection page experiences by giving librarians tools to create custom collection pages and tag and organize books in bulk.

- Improving Read Aloud by using AI to generate more natural/human voices, make the feature more discoverable in the bookreader interface, and fix read aloud navigation so it works more predictably.

- Allowing educators to easily convert their syllabi to lists on Open Library using a Bulk Search & List creator feature.

- Moving to a smarter, simpler omni-search experience that doesn’t require patrons to switch modes in order to get the search results they want.

- Importing missing metadata and improving incomplete records by giving more librarians better tools for adding importers and identifying records with missing fields.

- Improving the performance and speed of the service so it works better for more patrons in more areas.

About the Process

The Open Library team was fortunate to benefit from the guidance and leadership of Abbey Ripstra, a Human-Centered Design Researcher who formerly led Design Research efforts at the Wikimedia organization. This research effort wouldn’t have been achievable without her help and we’re grateful.

In preparation for our research, Abbey helped us outline a design process using an online collaboration and presentation tool called Mural.

During the planning process, we clarified five questions:

- What are the objectives of our research?

- How will we reach and identify the right people to speak with?

- What questions will we ask interview participants?

- How will we collate results across participants and synthesize useful output?

- How can we make participants feel comfortable and appreciated?

To answer these questions, we:

- Developed a Screener Survey survey which we rendered to patrons who were logged in to OpenLibrary.org. In total, 466 patrons from all over the world completed the survey, from which we identified 9 promising candidates to interview. Candidates were selected in such a way as to maximize the diversity of academic topics, coverage of geographies, and roles within academia.

- We followed up with each candidate over email to confirm their interest in participating, suggesting meeting times, and then sent amenable participants our Welcome Letter and details of our Consent Process.

- We coordinated interview times, delegated interview and note taking responsibilities, and kept track of the state of each candidate in the process using an Operations Tracker we built using Google Sheets:

- During each interview, the elected interviewer followed our Interviewer’s Guide while the note taker took notes. At the end of each interview, we tidied up our notes and debriefed by adding the most salient notes to a shared mural board.

- When the interviewing stage had concluded, we sent thank you notes and small thank you gifts to participants. Our design team then convened to cluster insights across interviews and surface noteworthy learnings.